MOVEMENT RESTRICTIONS

THE LUCKY ONES HAVE A PERMIT TO LEAVE THEIR SQUALOR TO WORK IN ISRAEL'S CITIES, BUT THEIR LUCK RUNS OUT WHEN SECURITY CLOSES ALL CHECKPOINTS, PARALYSING AN ENTIRE PEOPLE.

ARCH-BISHOP DESMOND TUTU

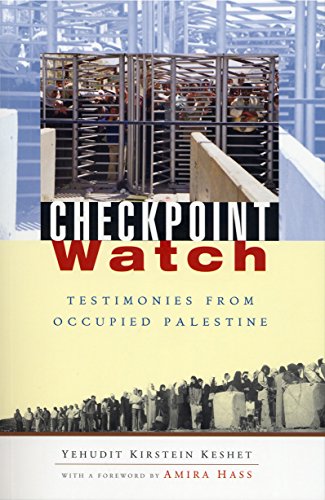

Noor was excited but nervous. She had never visited Jerusalem in her life, but she had finally applied for an Israeli permit to visit the holy city and see the stones of the Old City and the iconic Dome of the Rock, just a few miles from her West Bank village. To her surprise, she had received it. She took a bus to the Qalandia checkpoint, where hundreds of people waited in cage-like metal chutes.

When she was finally at the front of the line, the metal door buzzed her through to a chamber where young female Israeli soldiers sat on the other side of bulletproof glass. Noor held up her ID and permit. The soldier squinted at them and looked at her dubiously. She said something in Hebrew, and another soldier motioned for Noor to enter a different room where she was strip-searched, her bags dumped on a table and searched.

After several minutes of interrogation, she was told to go back where she came from. She realized with a sinking feeling that she may never see Jerusalem in her lifetime.

In fact, the majority of Palestinians, both in Palestine and around the world, are unable to visit Jerusalem due to Israeli restrictions on movement.

Starting in 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza, the territories were declared a closed military area, and freedom of movement was severely limited. In 1972 these restrictions were largely lifted, but in the 1990s, partially in retaliation for the mostly non-violent first Intifada, Israel began requiring military-issued permits for Palestinians wishing to travel to Israel or between the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza.

The permit regime was formalized as part of the Oslo Accords. The Accords also divided the West Bank into ‘islands’ of partial Palestinian control called Areas A and B that made up 40% of the West Bank. Area C, under full Israeli control, comprised the other 60%.

Even before the second Intifada started in September 2000, the Israeli army began imposing movement restrictions that made it more difficult to move within the West Bank from one ‘island’ to another. When the second Intifada began, Israel intensified its policies of closure via an internal system of restrictions comprised of hundreds of checkpoints, road blocks, gates, earth barriers, settler-only roads, and the Wall.

These barriers particularly impeded Palestinian access to areas like East Jerusalem, the Jordan Valley, lands isolated from their owners by the Wall, and the settlements in central Hebron, which Israel is interested in annexing permanently in violation of international law. Among the most absurd permits are those required for land owners to access their own land if it falls to the west of the Wall. More than half of such permits are denied.

Among the most coveted permits are those that allow one to visit East Jerusalem, Palestine’s spiritual and cultural capital, which can be extremely difficult to obtain. They permit only day trips; you need a special extra permit to stay the night. Even with the correct permit, one always faces the possibility of being turned back at a checkpoint without explanation.

In addition, the Israeli government engages frequently in general movement restrictions that amount to collective punishment. After an attack in Tel Aviv by two Palestinian gunmen that killed four, Israel froze permits for more than 80,000 Palestinians to visit relatives or pray in Jerusalem during Ramadan. The army also sealed the suspected gunmen’s village in the West Bank completely, meaning entry or exit would only be permitted for humanitarian and medical cases. Thus Israel has the power to detain entire villages. If it wishes, the Israeli army can put the entire West Bank on lockdown; this can be done within hours by closing all checkpoints and sealing the Wall.

For Palestinians living outside of Palestine, traveling to their homeland can be difficult or impossible. Israel decides at the borders whom to let in and whom to ban. Even an American passport is no guarantee of being allowed to visit the Palestinian homeland. Each year dozens of Palestinians from around the world are denied entry on arbitrary or unknown grounds.

All of these restrictions create an atmosphere of near-constant uncertainty for Palestinians trying to go about their daily lives. Being forced to endure complex bureaucratic hassles with no guarantees just to move around deprives many Palestinians of their right to work, to health, to education, and to a stable family life.

The Gaza Siege imposes incredible barriers to movement for the residents of Gaza, and it’s nearly impossible for Palestinians to travel between the West Bank and Gaza. Residents of the West Bank and Gaza also must apply for permits to travel abroad or enter Israel, including for needed medical treatment. Obtaining these permits is, likewise, an onerous hassle with a dubious chance of success.

Israel is entitled to protect itself by necessary means. But given the overwhelming and near-constant nature of the restrictions, regardless of the security situation, and the grievous harm they cause to millions of innocent people, Israel’s policy of movement restrictions constitutes blatantly discriminatory collective punishment and a grave breach of its obligations as an occupying power under international law.

The checkpoints during the past six months and the new procedures from the occupation has made life very difficult for Palestinians, we feel it a lot.

Reham Abu AitaPermits are a political weapon to force Palestinians into accepting short-term economic improvements over long-term territorial and political solutions.

Amal Jamal- Professor at Tel Aviv UniversityI live ten minutes from here. But now it takes an hour to reach my home because of the checkpoints.

Mahmoud Elayan